I am the German Vice-Champion in Science Slam 2021! I’m really happy and think this is a great opportunity to take you with me into the world of the Science Slam. Hopefully, I can answer some of the most frequently asked questions about Science Slam and maybe I can motivate some of you to venture on stage and share your hard-earned research with the world.

Let’s start with a short explanation for those to whom Science Slam means nothing. Science Slam is about explaining science clearly and engagingly on stage in a short period of time; usually 10 minutes. Tools and props are allowed! The basic equipment is a presentation with illustrations – from self-drawn masterpieces to the well-known internet meme – that is both uproariously funny and illustrates complex science. Sometimes people perform experiments live on stage, play music or juggle – whatever helps is allowed! The basic idea of Science Slam is that scientists bring their research out of the “lab” onto the stage and to the audience. All scientific disciplines are represented, including those that have nothing to do with laboratories.

In many cases, it is a rule that the speakers have to talk about their own research. That means that even if I find astrophysics exciting and know everything about it, I’m not allowed to present it at most Science Slams. That’s why it goes without saying that the presenters at such Slams, which are based on original research, are scientists (or at least used to be). However, the results don’t have to be published – you can also compete in a Science Slam with the topic of your Bachelor’s thesis!

Battle of the scientists

There is one point I haven’t touched on yet: the Slam. To slam can mean to move against a hard surface with force and usually a loud noise. But that is not quite what we mean – nobody is thrown against a wall. Alternatively, to slam someone also means to criticise severely. In simpler words: a Slam is a competition. Things are (usually) not quite that tough, but Science Slam is still a competition. After the presentations, the audience votes on which presentation they liked best. There are a variety of methods for doing this: either with score cards, with the volume of applause, matches or marbles thrown into various containers, or – in pandemic times – online voting.

But the motto of Science Slam is: it’s not about winning, it’s about the science. Of course, I’m happy when I win, but winning doesn’t really change much. The prizes at the Science Slam are more symbolic: books (scientific, of course, and usually related to the event), wine, mugs, a board game, fridge magnets and of course: fame and glory. Only once have I seen a cash prize in the three- to four-figure range. The slam was supported by a research project.

Career wish: Science Slam?

Talking about money: Do you actually get paid for it? Can you make a living from the Science Slam? Simple answer: Nope (at least not exclusively). For one thing, because Science Slams don’t happen often enough to fill a full-time job. For another, many Slams are unpaid. At least the accommodation and travel costs are usually paid, so as an occasional travel option, it might be suitable. But in rare cases there isn’t even that: one time I spent the night on a folding bed in a dressing room backstage at a cultural centre. It wasn’t as bad as it sounds though, it was actually quite nice there and the mirror gave off a touch of glamour.

Fortunately, many science slams are paid – a small remuneration of 100€ is common. In some cases, you get more, especially if there are clients who want to hold a Science Slam at their venue or event. For example, I once gave a talk in Science-Slam-style at the award ceremony for a quantum physics prize; then I got a bit more. But something like that is rather the exception, at least for me. Maybe that will change with the vice title (call me!).

From Poetry to Science Slam

Before I tell more anecdotes, let’s dive a bit into history. Really just a bit, I promise, because there really isn’t much to say. Science Slam is derived from Poetry Slam. The latter works in exactly the same way as Science Slam, only – surprise – it’s about poetry. In most cases, however, props are forbidden and the performance time is shorter. Poetry slam originated in the USA in 1986 and became popular worldwide in the 1990s, especially in Germany. Since 2016, poetry slam has officially been a UNESCO intangible cultural heritage. Just like German bread culture, star singing and the preparation and use of traditional lime mortar. The more you know.

That’s all I want to say about Poetry Slam because I don’t really know anything about it. The first Science Slam was organised by poetry slammer Alex Dreppec in Darmstadt in 2006, and from 2008 it was continued and spread by Markus Weißkopf of the Haus der Wissenschaft Braunschweig. In the meantime, there is even a (German) scientific book on Science Slam to which both of them have contributed. Unfortunately, I don’t have it myself, otherwise I could quote eloquently from it now, but maybe I’ll do that later!

Today there are Science Slams in many German cities. The two biggest organisers are Science-Slam.com and ScienceSlam.de but Science Slams are often also organised “unofficially” by other people and groups. The biggest Science Slam so far took place in Wiesbaden and had 4600 visitors – how incredible and wonderful that so many people are interested in science! By the way, this big event was nothing other than the German Science Slam Championship 2018. Science-Slam.com has been organising a German championship since 2010 where for example Reinhard Remfort from the popular German podcast Methodisch Inkorrekt won in 2013. This year, I came in second place and was thus runner-up behind the wonderful Janine Moyer!

An unexpected journey

I actually only started with Science Slam last year. My first Slam was the Q-Science Slam by the University of Stuttgart in February 2020 which I can only recommend, both for slammers and for the audience. As the name suggests, it’s all about quantum physics – if that’s not reason enough! In addition, there is be a preparation workshop including voice training and dramaturgy tips. Especially new slammers are in good hands and the final slams are on a high level – a great show for the audience!

And then came the pandemic and with it dark times for entertainers and artists. No question about it: for me, Science Slam is a hobby; professional artists have been hit much harder. But after I had first walked on stage, I had to take six months off. After that, I fortunately had the opportunity to go on stage every now and then; sometimes with an audience, but mostly without.

That was not only a pity for the actual Slams but also because of the social component, because science slams are always super fun apart from the stage experience. I often sit on the train on the way to the slam, slightly shivering and excited, and as soon as I arrive and chat and joke around with my fellow participants, the excitement subsides. After the event, we sit together, drink beer, eat pizza and have a good time. Sometimes in a club, sometimes with a ukulele in the craft corner of a museum. No trace of competition.

The championship

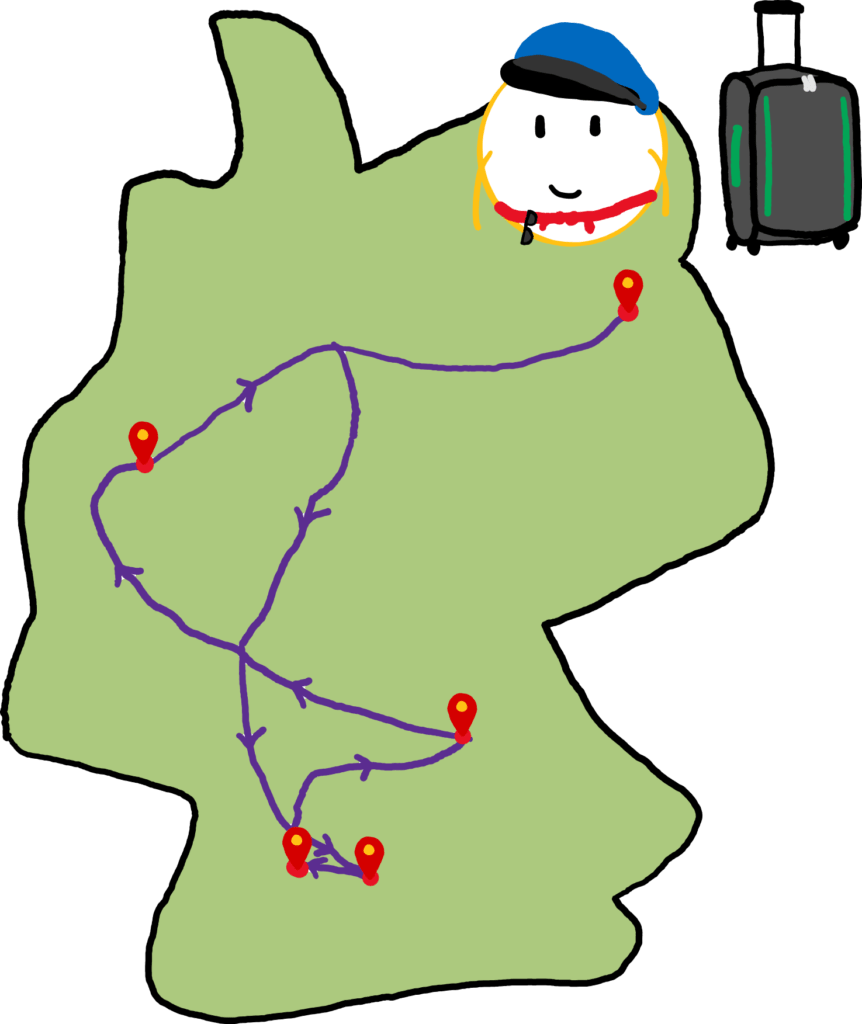

As you might have seen on social media, I had a busy week just before the championships. I competed in four Slams in five days – covering a good 2300km distance. The timing was actually more or less coincidental. It wasn’t an “official warm-up week” but probably more “pandemic last-minute panic”. I have to admit: the week was tough. I used to travel a lot because of my research but with the pandemic, my globetrotting gene has gone to sleep. Even though the nervousness before performances has reduced by now, I am still tense. In addition, the evenings are long, we sleep in unfamiliar beds and have probably had an hour-long train journey with delays or cancellations.

Accordingly, I was no longer completely fresh when I arrived at the final. On top of that, there were technical problems with the live stream. At eight o’clock we were ready to go at the edge of the stage. More precisely: in a small fake basement with unfortunately-not-quite-so-fake spiders, in order to euphorically run up the stairs and onto the stage at the right moment. As if! We stood down there for a quarter of an hour before we were told that the stream wasn’t working and that we should come back up first. Then we waited. Then the announcement: the stream wasn’t working, we would be recording. One minute later: Yes, it works, hop down, here we go! We go from zero to one hundred, wait downstairs, run upstairs at the wrong moment, the stream doesn’t work after all, and finally, our fantastic stage entrance is cut out. Emotional rollercoaster!

Our slams all went well in the end, we all stayed within the time limit. It wasn’t my best performance and I got muddled in a few places but considering the circumstances, we all did our best. In the end, it seemed to be enough because I became vice-champion! A big thank you to everyone who voted for me – I would bet that I owe part of it to you, my readers!

What happens now? For the moment, unfortunately: nothing at all. The pandemic is once again making life difficult for us. I already have two dates for February and March but will they be able to take place? We will see. But if they do, I hope I’ll be able to tell you about control-addicted scientists, mutated vegetables and dancing atoms as a newly baked doctor of physics.

Do you like what you read? On YouTube you can find a playlist with all my recorded Science Slams (one of them in English!). And if you like, you can buy me a coffee here! If you don’t want to miss any new posts, don’t forget to subscribe to my blog.