It’s over! Six months after submitting my doctoral thesis, 5 years after starting my doctorate, 10.5 years after my first day at university – doctor rerum naturalium! The end boss is defeated, the disputation is over! And of course, I want to share with you what this defence is all about, how I prepared for it and also how disputations can differ from one another.

One piece of information in advance: If you are generally interested in the topic of doctoral studies in physics, these two articles might also be something for you:

- Doctor-What? Career fair with Dr. Doom, Dr. No and Co. is about doctorates in general: what do you do all the time and what does it mean to have a doctorate?

- A whiff of stress – the doctoral thesis is about the process of writing the PhD thesis.

This article, the last in this series, for the time being, is about the defence. And here, too, is a disclaimer: I am talking about my experiences and those of other physicists. In other subjects (and even at other universities), the procedure can differ considerably.

Between thesis and defence

The reports

Six months ago I handed in my PhD thesis and now I had my defence. What takes so long, you ask? Very good question; I also asked myself that every day. Usually, two to six months pass between the submission of the doctoral thesis and the defence. During this time, the referees read the thesis and evaluate it. These are often two professors, one of whom is the doctoral supervisor.

In other countries, this might differ. In Spain, for example, the supervisor is not involved in the grading process. This sounds reasonable at first because this person is biased and might want to give you a better grade than a stranger. On the other hand, the supervisor knows your work and the research area best and can assess very well how important the contribution to the field actually was. The grading by two reviewers serves as an additional safeguard to prevent cheating.

The grading system

Some universities have even more precautions. At the Free University of Berlin, you can only receive the top grade summa cum laude (“with highest praise”) if both reviewers have awarded it. In this case, an additional, external third reviewer is requested and only if this reviewer also awards the top grade you have a chance.

Usually, the grades are: summa cum laude (“With highest praise”), magna cum laude (“With high praise”), cum laude (“With praise”), rite (“sufficient”) and not passed. The FU Berlin has abolished these grade levels – here there is only summa cum laude, passed and failed, because in practice almost exclusively summa and magna are awarded anyway.

The display period

As soon as the reviews of the doctoral thesis are available, the thesis must be publicly displayed. This means that members of the department with a doctorate (in my case: physicists with a doctorate from the FU Berlin) can look at my work and complain if they think something is wrong. Pure formality – who reads through random doctoral theses to then complain? As a result, doctoral candidates have to wait between two and four weeks (in my case, of course, it was four) for things to progress: you can set a date for the defence.

The defence

We’re getting down to the point. So what is this “defence”? Who is defending what? Are there duelling weapons? (The answer will surprise you!)

At the end of the doctorate (and at some universities also at the end of the Bachelor’s or Master’s programme, as was the case for me at Kassel), you have to defend your work literally. This is formally called a disputation and is a scientific debate. You present, discuss and, yes, defend your work in front of an examination board consisting of about five people, most of them professors (in my case: two professors, a senior researcher, a postdoc and a doctoral student). In addition, the disputation is public, which means that colleagues, friends and family can watch.

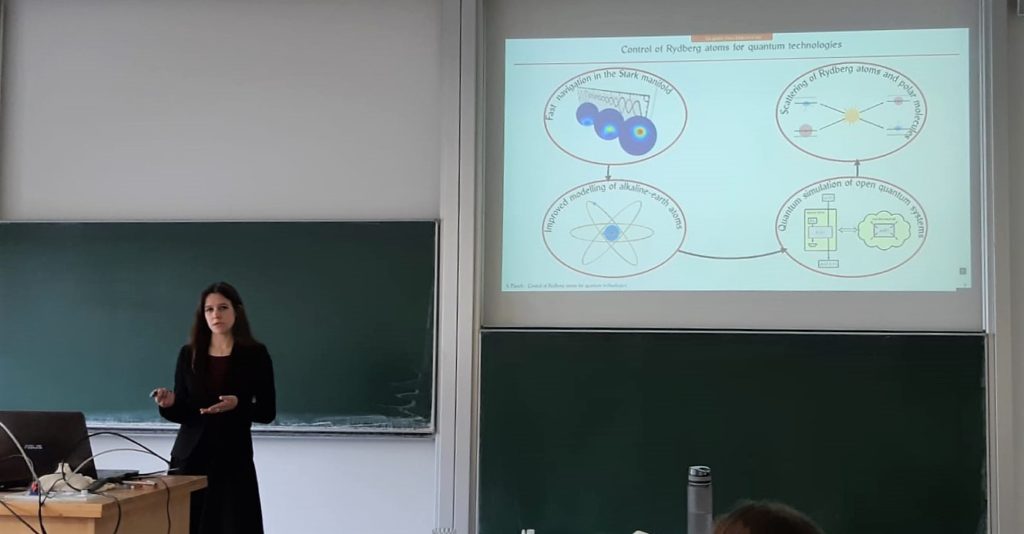

Round 1 – The presentation

At the beginning of the defence, the student presents a 30-minute talk in which they present their research results. 5 years of research in 30 minutes – that doesn’t just sound ambitious, it is. That’s why I only presented two of my four research topics, for example, and only the most important results. There is no time for technical details and step-by-step explanations.

Round 2 – Specific questions

Then the cross-examination begins. First, the commission asks specific questions about the work for 30 minutes. How did you do it? Can you do it differently? Why did you use this method and not the other? What were you thinking? How can I understand this? Here, the examiners want to see that the candidate has understood and thought through what they were doing, and can justify and explain it. If they have found problems in your work, these will also be discussed.

Round 3 – Broad questions

In the last 30 minutes, the focus is loosened and broader questions are asked about the research area or, in principle, about any topic in physics. This can be moderate (“How does your system behave compared to other systems?”), abstract (“Speaking of matter, what do you think happens if I hold a piece of dark matter in my hand and drop it?”) or absurd (“How could I create complex quantum mechanical states using a laser pointer?”).

This part is the most terrifying because you can hardly prepare for it. Some questions you can guess, others you would never have expected in your wildest dreams. In this part, the examiners want to find out whether you live in your small research bubble or whether you also know about general physics and other research topics. The better your grade, the harder the questions. The board wants to see you sweat. They want to find out if you can think spontaneously about questions you don’t know the answer to. It is not unlikely that the examiners will not know the answer themselves.

Preparation

Now that you know what happens in the disputation, you may be wondering: how do you prepare for it? There are two aspects: the technical and the mental preparation, which often take several months.

Technical preparation

Everyone prepares differently for this challenge. I started in January, hoping my defence would be in mid-February. In the end, it was in April… But of course, time doesn’t stand still – university life and work went on alongside.

First, I prepared the actual presentation for the defence and read some background literature on the respective topic. Afterwards, I repeated my Bachelor’s degree in a fast-track manner. In just under four weeks, I went through all the basic lectures in theoretical physics in order to be prepared for general physics questions. The probability that I will be asked to write down Maxwell’s equations (the basic equations of electrodynamics) is perhaps small. But if it does happen, you don’t want to embarrass yourself!

In the last two weeks before the defence, it was down to the wire. Due to external, unfortunate circumstances (cough cough, COVID), I had less time for final preparation than I had hoped, despite the long waiting period. During this phase, I re-read my own thesis and literature (i.e. scientific publications) on topics I was unsure about, as well as review articles that dealt with the “big picture”, in order to prepare for the second round of questions. I tried to imagine which nasty questions I wouldn’t be able to answer (the more you study, the more questions arise – it’s a vicious circle).

Mental preparation

Looking back, I can say: 90% of my preparations were unnecessary. Nobody asked me about Maxwell’s equations. Instead, I was asked about other topics that I actually wanted to read up on but didn’t have time to. Nevertheless, it is good for your own sense of security to prepare thoroughly. You know you have prepared yourself. The repetition of the basics was also useful – you forget very quickly!

Looking back, would I do it differently? No. You can’t know what questions the examiners will spontaneously think of. No matter how long you prepare, you can’t know everything. No one can, not even the professors. Instead, have confidence that you have actually learned a bit about research in the last 5 years – and that you actually are an expert!

What has also helped me is to internalise: No one means me any harm. Yes, you are being tested, but no one wants to see you fail. You have proven with your thesis that you are worthy of a doctorate. As long as your supervisors are not diabolical beings from the fifth circle of hell, they want you to pass.

Aftershow-Party

Some people say that the disputation is ultimately just a show. The examiners already knew what grade you’re going to get, they just want to see it confirmed. It didn’t seem that way to me when I was standing there in front, but in retrospect, that’s certainly not entirely wrong. It would even be unfair if a single exam should diminish your performance over the last 5 years. It’s almost impossible to fail, as long as you show that you’re making an effort.

The disputation is a celebration. Everyone dresses up, there’s a buffet (which, admittedly, you have to organise yourself) and you toast the end of a year-long journey. In Germany, we don’t have a traditional doctor’s outfit with a doctor’s hat and gown – we have something better (or at least more personal)!

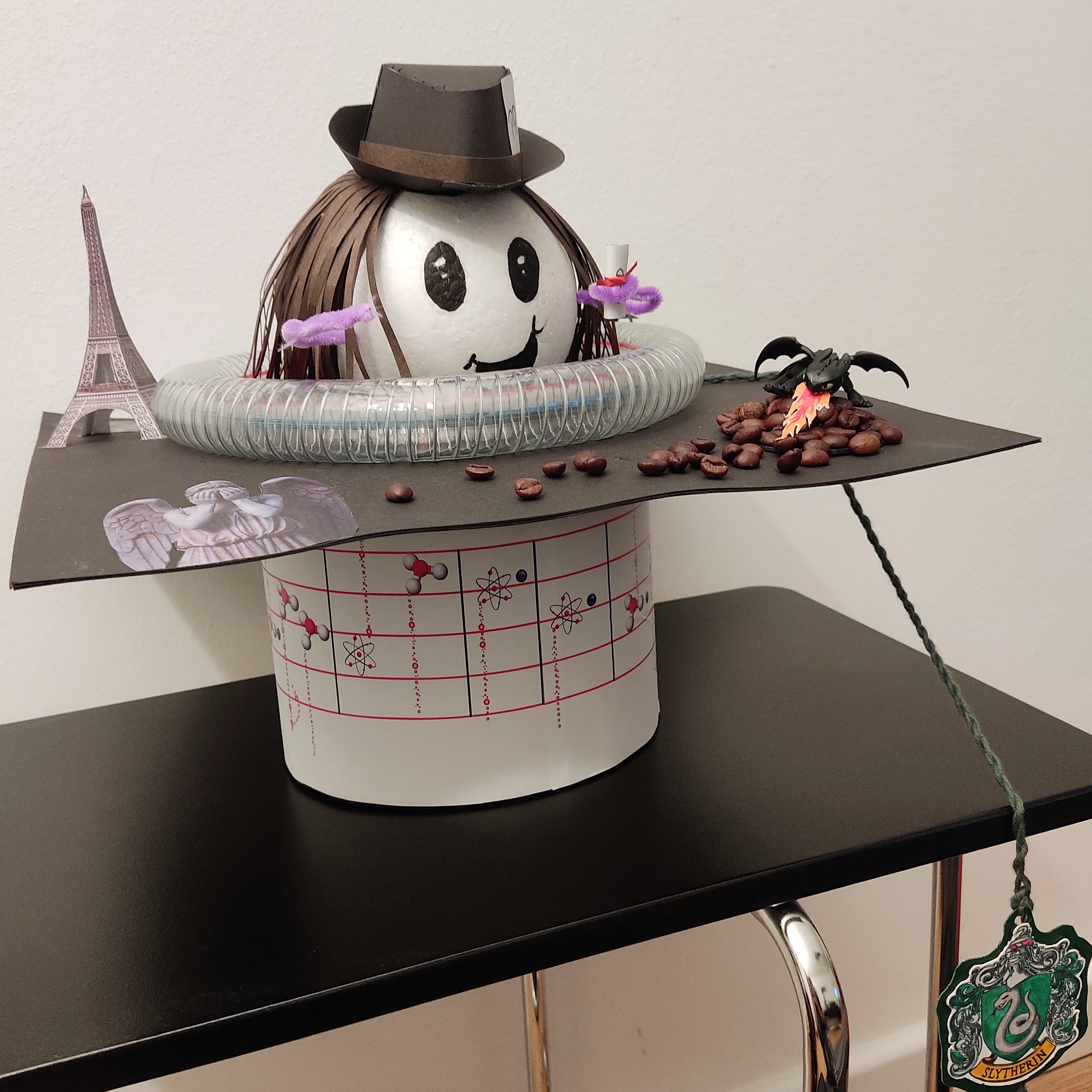

The doctor hat

It is a tradition that the other doctoral students in the research group make a doctoral hat for the newly graduated doctor with their own hands! You can imagine that a group of theoretical physicists has already damaged one or two fingers while cutting paper. But they don’t just make a hat, they also decorate it with personal objects or pictures that allude to their doctoral days. This hat is then ceremoniously awarded directly after the grade is announced.

A few examples of what was on my hat: In the centre, there is a round figure with a hat (hat-ception). The hat is, as I’m sure you all recognised, a journalist’s hat, which alludes to my writing. The figurine is also surrounded by a tube in which a blue ball is rolling – an electron! This represents the circular Rydberg atoms I work with, which look like a hula-hoop (those who know my science slam on dancing atoms will recognise the ballerina atom). There are also some Harry Potter references on my hat because I am a passionate Harry Potter fan. But I don’t want to give it all away and maybe you can guess some of the references on your own!

Other countries, other customs

The disputation differs from university to university and from department to department. I can’t say much about how a disputation in psychology works – there are better people to talk to than me. There are also alternatives to the disputation. But I’m not familiar with those either, because I’ve never met anyone who’s done anything like that. However, I do know a few anecdotes about how the disputation looks in other countries, which I don’t want to withhold from you:

- Finland: PhDs are traditionally awarded a hat and a sword after their defence. They symbolise the freedom of research and the fight for what is good, right and true (I promised you weapons, here they are!). In return, the doctoral candidates also have to defend themselves for a few hours(!).

- Netherlands: PhD students appoint two people as “jokers” (paranimfen) to step in if they are not comfortable or if physical altercations occur – like seconds in a duel. Fortunately, this position is now mainly symbolic.

- Argentina: After the defence, it is traditional for family and friends to throw paint, eggs, flour or confetti at the graduates. Usually, however, they are prepared for this and put on old clothes beforehand. For men, it is also traditional to cut off their hair. However, this is no longer followed by everyone and sometimes only a small piece of hair is cut symbolically.

Do you know any other customs or traditions? What was your experience of doing your doctorate? If you have a doctorate, what was on your doctoral hat? Let me know!

Do you like what you read? Then maybe you also like my other articles from the series “How to PhD“. And if you want you can buy me a coffee here! Don’t forget to subscribe to my blog if you don’t want to miss any new post.

Your science slam brought me here and I never talked to someone who had a doctor describing the process to me so I was curious to read the blog post. Thanks.