It’s 8th of March and that means: it’s International Women’s Day! In Berlin, it’s even a public holiday! This year’s motto is #BreakTheBias – for a world free of stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination. As a woman in physics, you can be sure that I can say something about this subject. Today, I don’t want to feed you too many numbers (there are plenty on the web), but rather tell you about my own personal experiences.

Let’s brainstorm on the topic of stereotypes and prejudices regarding women in physics:

“Girls are worse at maths.”

You can probably guess: I was good at maths and physics at school. And yes, I was in rather male company in the physics and maths advanced course. An exception, one might think. Unfortunately, the Pisa study, for example, actually shows that girls do worse on average in maths than boys. But this is not because female brains have a problem with maths, but in my opinion (and that of many scientists) because of bad role stereotypes. Because girls are told they are worse at maths, they become worse at maths. Because “it’s ok” to be bad at maths as a girl (sources and more on this here – in German).

“You don’t look like a physicist.”

Honestly, what does a physicist look like? With wild white hair and a stuck-out tongue? Even my male colleagues don’t look like that. Female physicists are stereotyped as tomboys or mousy persons. Sure, they exist in physics – just like any other style. My appearance has nothing to do with how good I am at physics. Full stop.

“Physicists are socially incompetent nerds.”

This applies to men and women, of course. Keyword: Big Bang Theory. The series has done a lot for physics – both good and bad. Physics has become socially acceptable, nerdy is cool, people know who Schrödinger’s cat is. But: Almost all physicists in Big Bang Theory are nerdy and male. The women in the series are either biologists or (sorry Penny) silly. One of the few exceptions: Leslie Winkle. She appears more often in the first three seasons but then disappears. She is tough and does not fit the physicist stereotype. Unfortunately, her role in the series focuses on (more or less) romantic relationships with the guys. Just like every other female physicist who appears in the series.

Need for renovation in science: leaky pipelines and glass ceilings

Let’s leave the flat stereotypes and get down to the nitty-gritty. There are problems in science, and not only in physics. One is visualised by the leaky pipeline. At the beginning of the academic journey, the proportion of men and women is almost equal (not in physics but spread across all disciplines; in physics, women make up for only around 20%). But the higher you climb the career ladder – from bachelor’s and master’s degrees, to PhD candidates and finally professorships – the proportion of women drops. Women drip out of the system like water from a brittle pipe. By the time they are appointed to professorships, only a good 36% remain.

Mind you: this is true across all disciplines! Even in biology, for example, where the proportion of women at the beginning of their studies is even higher than that of men, the ratio reverses towards higher career levels. This is also called the glass ceiling: after a certain point, women do not advance further, although there are no “obvious” barriers.

There are many reasons for this. In short: an unfavourable mixture of poor working conditions, discrimination and implicit bias (i.e. unconscious prejudices against certain groups of people) in academia. If young girls were watching “Germany’s Next Top Scientist” instead of GNT, maybe after 15 seasons we would also finally realise how broken the academic system is. But that’s a topic in itself and would go beyond the scope of this post. If you want to read more, you can visit the blog of the Lise-Meitner Society, for which I wrote an article on the topic.

From the life of a female physicist

You can read all about these topics in various studies, books or on the internet without ever having set foot in a physics lecture hall. But life is not a study. That’s why I want to tell you about my very own experiences as a woman in physics. First, an obvious disclaimer: the following are my experiences and I cannot speak for anyone else, certainly not for the entire female physics community. The list is inevitably incomplete.

Strong network

Positive news follows for the first time in this post: I am fine. I am not being attacked, excluded, discriminated against or harassed. Unfortunately, I know that this is different for other female physicists. I am part of a wonderful working group in which I have made many friends.

I should add that my supervising professor is a woman. I know from stories that this does not automatically lead to a women-friendly environment. But equality is important to her. She supports me and has a strong female network from which I also benefit. I know many female physicists, including many female professors, and unlike (male) professors, I am quite close to them. We greet each other with a hug, have a drink or have already been to the sauna together (clothed – not that close). Of course, this doesn’t apply to all the female professors I know, but among the men there are zero.

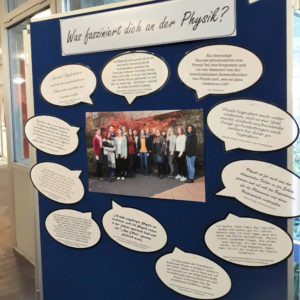

I was lucky enough to attend several women-only physics conferences. Without exception, the atmosphere was warmer and the hierarchy flatter than at mixed conferences. The focus was often on social issues: Working conditions in science, networking, soft skills. My male colleagues then asked me: Why don’t they have something like that at mixed conferences? Yes indeed, why not?

Tutoring for women

At my old university, there was occasionally a special course just for female physicists. I don’t remember the name (it was introduced after my student days), but it was basically a “tutoring” for female physicists in the first semesters.

Oh horror, are female students so bad that they need extra help? No, absolutely not. But since female students are exotic in the physics lecture hall, they stand out and we remember the “girls are bad at maths” prejudice. Some female students don’t feel comfortable asking questions because then they see the prejudice confirmed. The courses for female physicists are meant to provide a safe space where they can ask as many “stupid questions” as they want without feeling weirdly stared at. But some people think that these courses only reinforce the prejudice that women need extra help. Personally, I think anything that helps keep women in physics is worth it.

One consequence of all these prejudices is that women often feel they have to prove themselves extra strong. “Just as good” is not enough. I count myself among them. I am quite stubborn and I feel proud when I can prove that a woman is good at physics, maybe even the best in the course. As a result, however, one constantly puts more stress on oneself than perhaps is necessary.

What you deserve is what you get

The prejudice against women brings another hurdle with it: success is not acknowledged. I was often told that I only got a good (usually better) grade because I am a woman. Especially in oral exams, it is simply impossible to check such things. Some people also saw the fact that my professor allowed me to go to conferences for female physicists as preferential treatment. I can’t prove anything, but I don’t think I’m going out on a limb when I say that this is pure envy.

Success ist not only about grades but often more subtle. At physics conferences, there are poster sessions where (mostly young) scientists present their research and discuss it over beer and finger food. Obviously, you were successful at a poster session if your voice is ruined afterwards because you talked for three hours straight. Less successful were those who instead stared holes in the air and nibbled the label off their beer bottle because no one came to the poster. What makes a poster successful? Exciting results and an appealing visual appearance…. Wait, the poster or the person? According to some people, both. Again, I have heard the accusation that my poster was only so well attended because I am a woman.

Be a role model

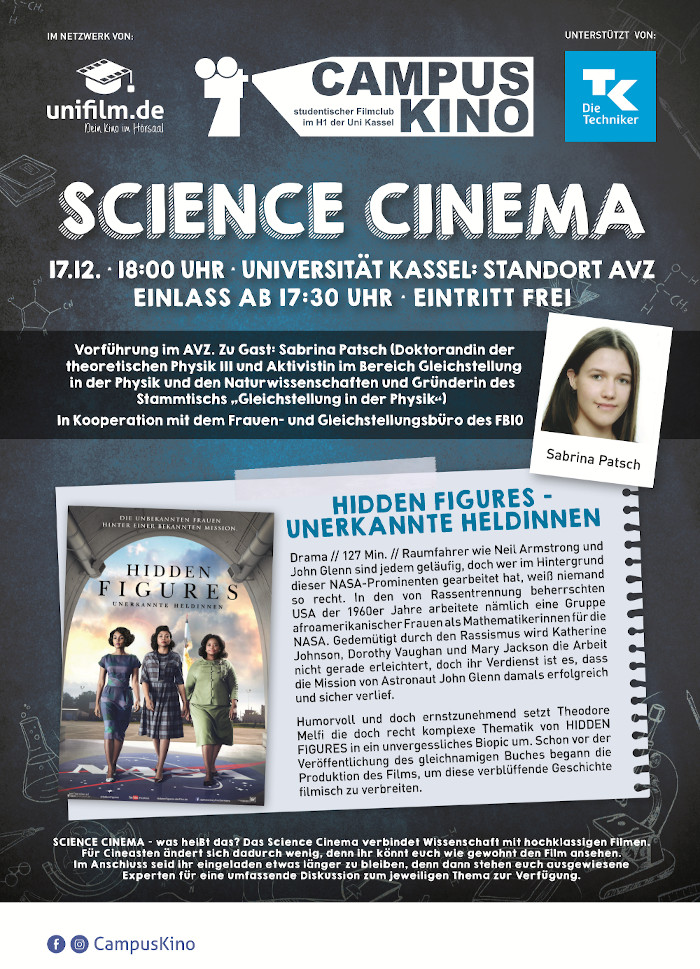

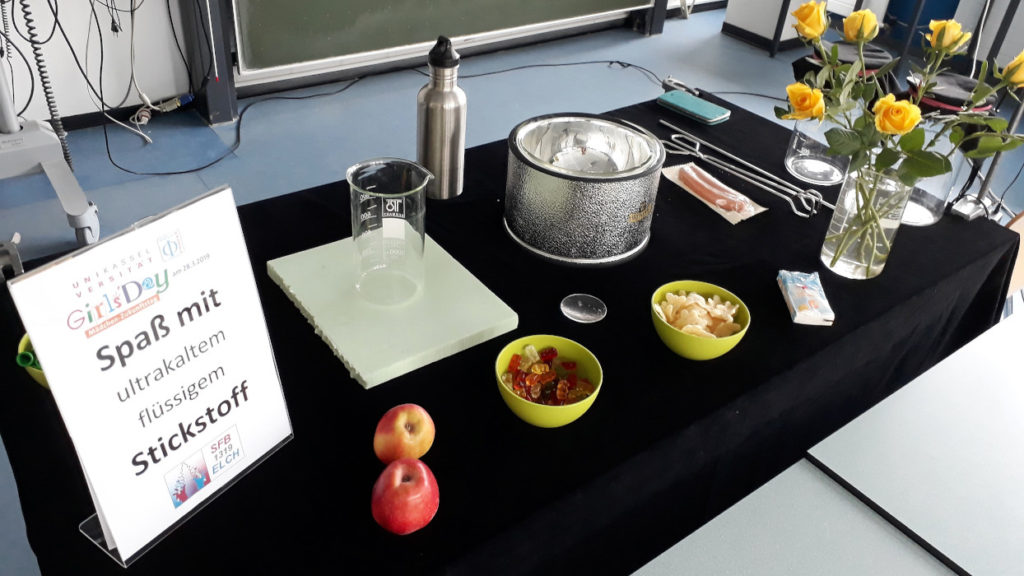

“Special treatment” like women’s conferences, however, works both ways. To promote women in physics, there are more and more special events (e.g. the Girls Day – if by chance any female 7th/8th grade students from Berlin are reading along: you can visit us!) or information stands at public events aimed at girls. And if you are the only woman in the group, who gets to take care of these things? Bingo!

Don’t get me wrong, I like doing this. I think it’s important. But it’s still extra work and if I didn’t do these things, no one would. Fortunately, I get support from my group here as well. But gender equality work is unfortunately mostly left to women. That’s the price we have to pay to provide role models for girls.

A single blog post cannot capture the full scope of the problem. The problem of equality is also closely linked to the general problems in academia and therefore need to be tackled together (see also my post on PhD studies and #IchbinHanna).

But one thing is a fact: as a woman in physics, you stand out. People remember me. Be it because I was one of five women at a conference, or maybe because I had red hair. You stand out from the crowd of nondescript, hoodie-wearing, white physicists (watch out: prejudice!). And if you want to forge a network and make a career, it helps immensely if people remember you.

Do you like what you read? Then you can buy me a coffee here! And if you don’t want to miss any new posts, don’t forget to subscribe to my blog.